Scything, soil, sheep and fruit

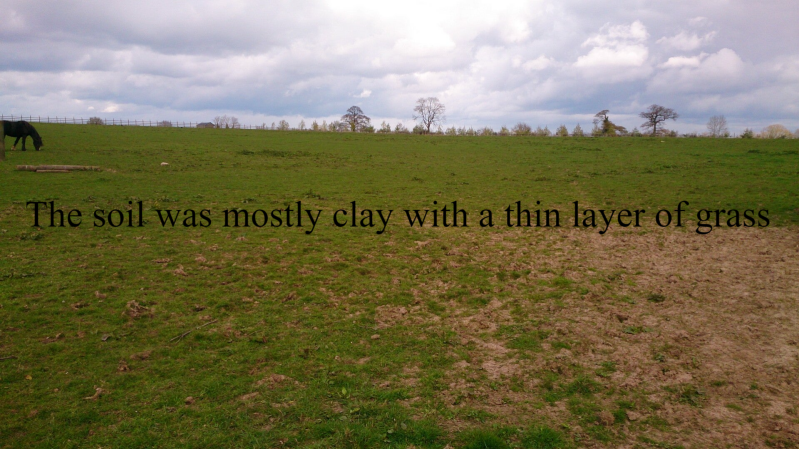

The original site was overgrazed clay soil with little or no humus. The first job was to evaluate the soil and water retention properties. My plan was to start the process of planting trees in zones and leave the rest to nature. Initially any rainfall resulted in rivers running off the field removing any chance of humus building up.

Clay soils hold water well but this site had nothing to prevent run off potentially undermining young trees. I also noticed when putting in saplings there were no worms. The ground was clearly compacted and although potentially fertile needed to breath.

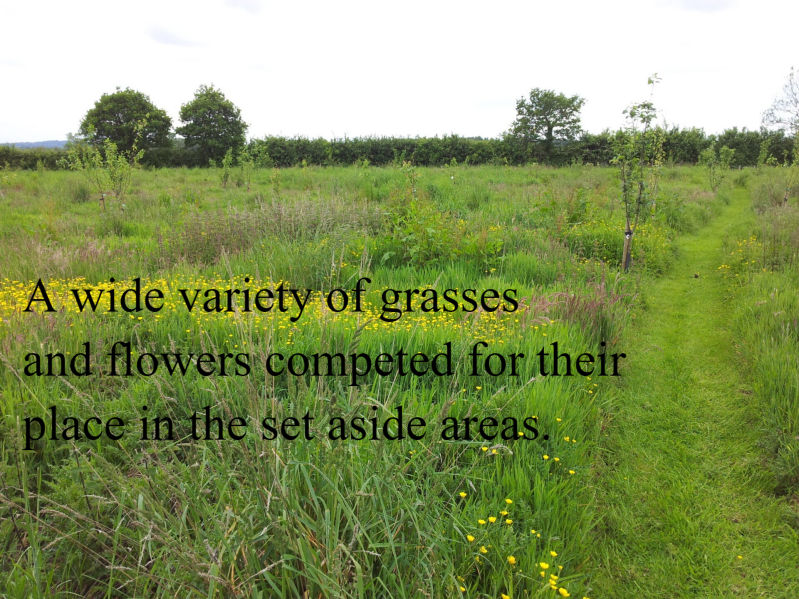

The dock, dandelions, creeping buttercup and clover played an important role in the early years creating aeration and breaking up the clay.

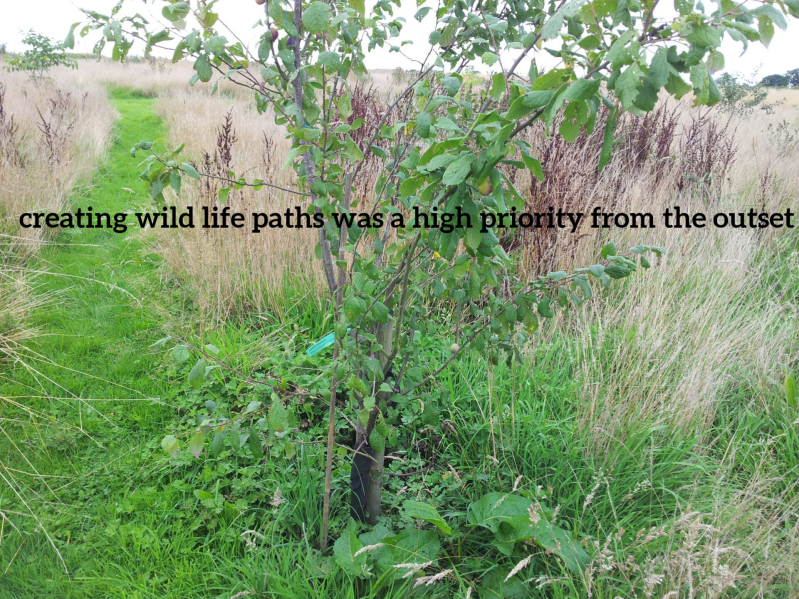

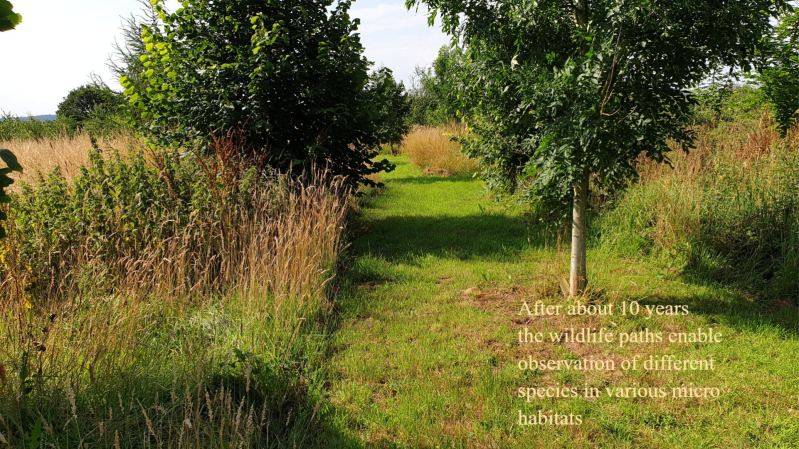

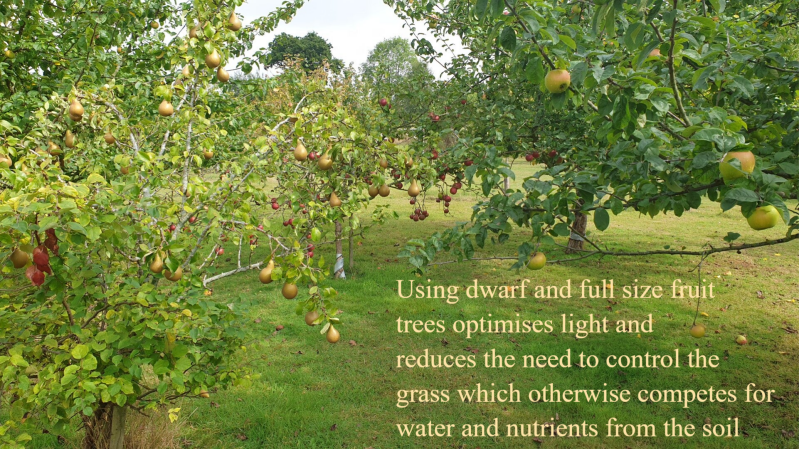

The site was split from the outset into orchard and wild areas but always with the goal of access and observation. Mechanical tools played their part but scything and sheep were used wherever possible.

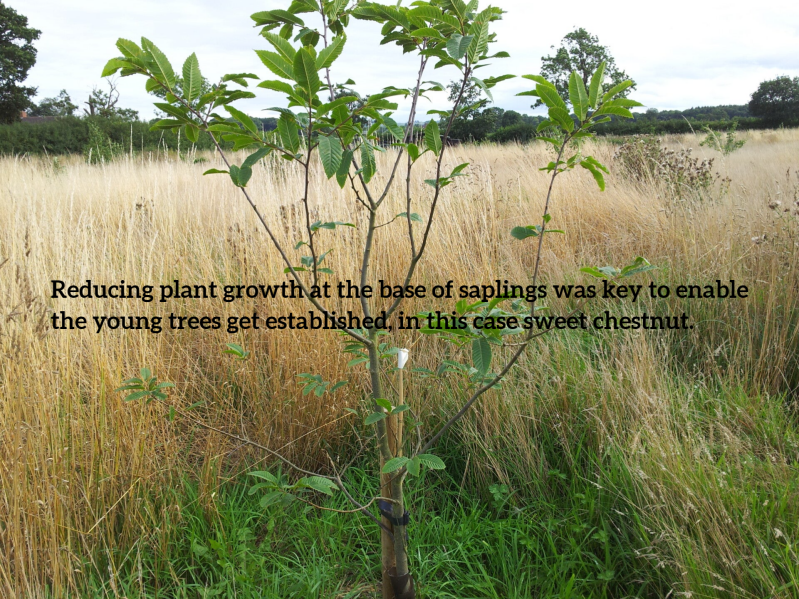

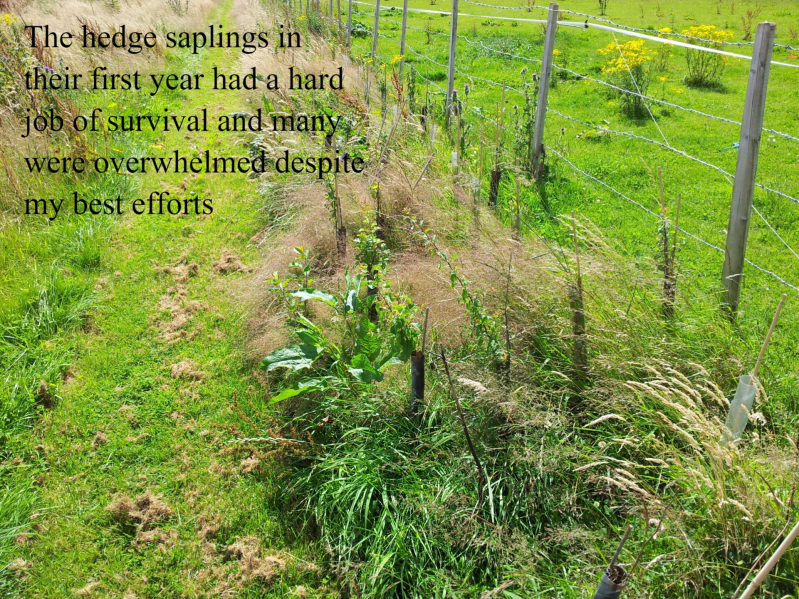

The 200m hedge required quite intensive clearance in the early years. The competition from grass and dock in particular meant many of the hardwood saplings were overwhelmed. The results however proved well worth the effort (below). Maintaining access required some mowing and trimming but if done regularly I found it manageable.

The arrival of Shropshire Sheep enabled further soil enrichment and the opportunity to implement seasonal grazing around the orchard and wildlife zones.

It was clear that using sheep could undermine diversity with trampling and selective grazing. However the ability to move the sheep around made it possible to minimise any negatives, improve soil and maintain paths using the sheep. They always choose grass to consume over other plants (apart from buttercups which they love).

The impact of scything was immense. It enabled me to build up organic matter far quicker than applying a fertiliser. The difficulty was the spreading of invasive plants and their seeds. I found that in winter the hoe could be used to remove excess dock and thistle easily. Grass always outcompeted others plants when given chance.

The sheep proved very useful in removing plants and grass at the base of young trees and Shropshires don't eat the bark of trees. This promoted more vigorous growth as sheep benefited soil nutrients with their droppings. The downside was trees damaged by the sheep rubbing themselves against the trunks. I lost many trees in the early years and even staking did not make much difference. The stronger the wooden stake supporting the tree the harder the sheep rubbed against it.

Wildlife ponds were created in various places to encourage wildlife and with primary woodland now established the arrival of foxes and owls was very rewarding.

The pathways form a network of different zones of conservation. I have used transitional management of conservation areas with some places strictly untrod or free from any control. Queen bees overwinter in loose soil or banks, anywhere that they can shelter undisturbed. To this end the site has many invertebrate hotels using stacked pallets with twigs, straw, bricks and even the sheep wool to provide potential crevices for bees and other insects.

I found it essential to use a petrol mower for the paths although this has been minimised. Ponds and different plant zones encourage different species at specific times of the year. From lots of butterflies feeding on overripe plums and damsons to dragonflies found on or around the four ponds. Below a strategically placed pallet protects one end of the pond from herons who will clear a pond of amphibians very quickly. Below you can just see a painted pallet covering one end of the pond. Without this protection the visiting heron would clear the pool of amphibians.

I indulged myself in some clear areas for picnics and playing tag with my children. These fruit trees are now many times larger so the games have changed to hide and seek.

The whole site has a network of hedges some planted others formed naturally from emerging woodland. Below - the hedge on the left is planted and the right side of the path is natural with a few pine trees that I added in the early years. I would estimate the original open field areas accounts for about 2 acres of the five original with grazing and paths making up transitionally managed grasses.

Bramble has formed a lot of protected areas proving relatively safe places for birds to nest and places for bees to over winter in the soil around the densely packed woody stems. It also has fruit for humans, wild mammals, birds and flowers for bees and other insects. It can be hard to control however and I have endured many injuries, in one case a thorn wedged in a finger joint that needed surgery.